Superfund Research Program

Environmental Factors Alter PFAS Removal by Specialized Nanomaterials

Release Date: 07/10/2024

![]() subscribe/listen via iTunes, download(5.6MB), Transcript(63KB)

subscribe/listen via iTunes, download(5.6MB), Transcript(63KB)

Researchers funded by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (SRP) revealed how characteristics of water treatment systems may alter the ability of novel nanomaterials to remove PFAS. Scientists should be aware of factors like water pH ' a measure of acidic or basic conditions ' or salt level to ensure that these nanomaterials effectively remove PFAS in aqueous environments, according to the team based at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

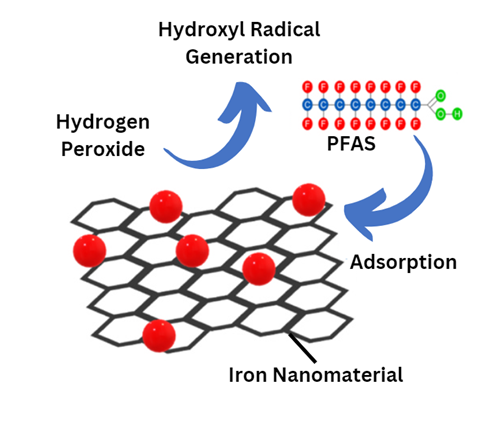

The researchers previously created a new approach that uses a novel nanomaterial ' made of tiny iron particles attached to a flat, carbon-based lattice called graphene ' that adsorbs, or traps, PFAS on its surface. Their approach involves adding hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which interacts with the iron nanomaterial to generate reactive molecules called hydroxyl radicals that destroy the strong molecular bonds in PFAS. This chemical process is called a Fenton reaction.

Setting Up Different Water Conditions

The team wanted to test how well their nanomaterial removed PFAS under different water conditions like high pH, high concentrations of salt, or the presence of natural organic matter.

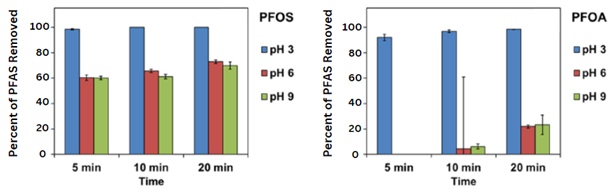

The scientists first tested the baseline performance of the nanomaterial by placing H2O2, the nanomaterial, and PFOA or PFOS in a vial of water. They shook the vial for 20 minutes, removing samples of the water at 5, 10, and 20 minutes. Then, the team repeated the approach over five different experiments, changing one aspect of the water chemistry each time. Specifically, they made changes to:

- pH level

- PFAS concentration

- Salt level

- Presence of organic matter

- H2O2 concentration

After finishing the experiments, the researchers assessed nanomaterial performance by analyzing PFAS concentrations in each sample. The scientists also tested for the presence of fluoride, acetate, and formate, which would indicate that the PFOA and PFOS had been degraded into their base components.

Emphasizing Water Chemistry in Remediation

Results showed that increasing the H2O2 concentration improved the nanomaterial's ability to remove PFAS. Additionally, the ability of the nanomaterial to adsorb PFAS decreased at higher concentrations of PFAS and higher pH levels. The presence of organic matter and higher salt levels also slightly decreased the efficacy of PFAS removal.

The analysis also detected fluoride, acetate, and formate in the samples, demonstrating that the nanomaterial removes PFAS by adsorbing and degrading PFAS molecules, the authors reported.

The study highlights the importance of understanding water chemistry when choosing this nanomaterial PFAS removal method, according to the researchers. Water systems with optimal conditions will allow this nanomaterial to work at maximum efficiency, they added.

For More Information Contact:

Diana S Aga

SUNY at Buffalo

611 Natural Sciences Complex

Buffalo, New York 14260

Phone: 716-645-4220

Email: dianaaga@buffalo.edu

Nirupam Aich

University of Nebraska

City Campus (Lincoln)

NH W150 E

Lincoln, Nebraska 68508

Phone: (402) 472-2371

Email: nirupam.aich@unl.edu

Ian Bradley

SUNY at Buffalo

220 Jarvis Hall

Buffalo, New York 14260

Phone: 716-645-4004

Email: ianbradl@buffalo.edu

To learn more about this research, please refer to the following sources:

- Ali M, Thapa U, Antle J, Tanim EU, Aguilar J, Bradley I, Aga DS, Aich N. 2024. Influence of water chemistry and operating parameters on PFOS/PFOA removal using rGO-nZVI nanohybrid. J Hazard Mater 5:469. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133912 PMID:38447366

To receive monthly mailings of the Research Briefs, send your email address to srpinfo@niehs.nih.gov.